Second chances have defined Chris Del Bosco’s career.

In 2004, Del Bosco, then 21, lay in a freezing creek in the dead of the Colorado winter. He had been attacked and left to himself in subzero water with a broken neck.

He shrieked for help, and someone heard the whimpering cry from the depths, eventually helping Del Bosco and getting in touch with his family.

To this day, the family and Del Bosco don’t know how it happened other than it could have been his death.

“We thought it could have been the end,” said Del Bosco’s sister, Heather Centruinoni, upon getting the phone call.

“We lived in constant fear. You might think this sounds overdramatic. But, trust me, it wasn’t. Think about losing a loved one. Imagine being powerless in the fight to help. People will tell you to let go, to move on, but we aren’t those types of people.”

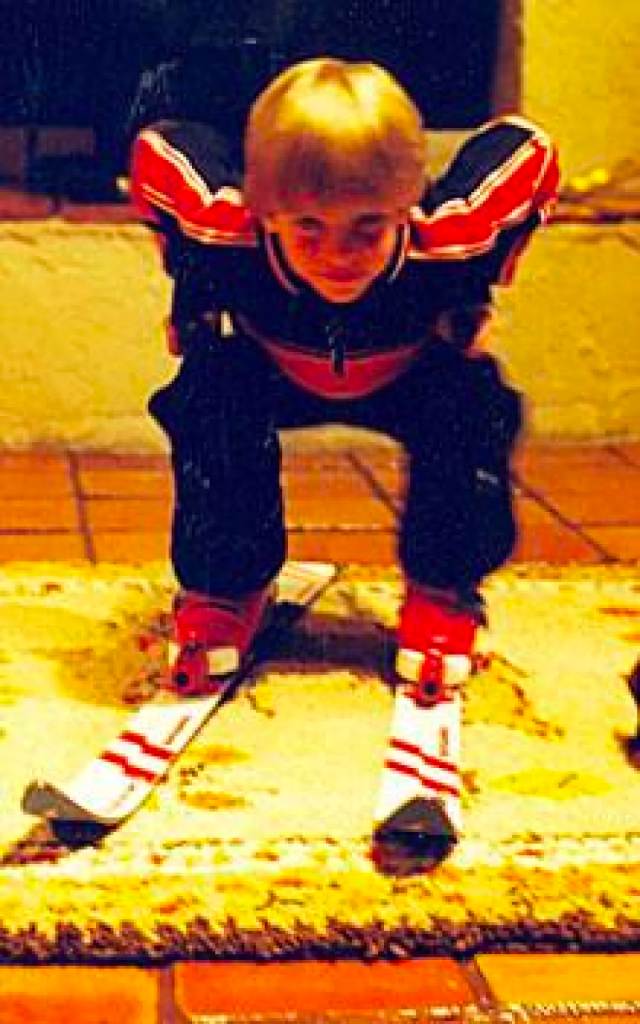

Del Bosco, now 40, was one of the top young American alpine ski racers, winning regional, state and national titles, before testing positive for THC marijuana at U.S. Nationals in 2000. Testing positive for the banned substance resulted in two years of suspension, pushing the then 17-year-old to the brink.

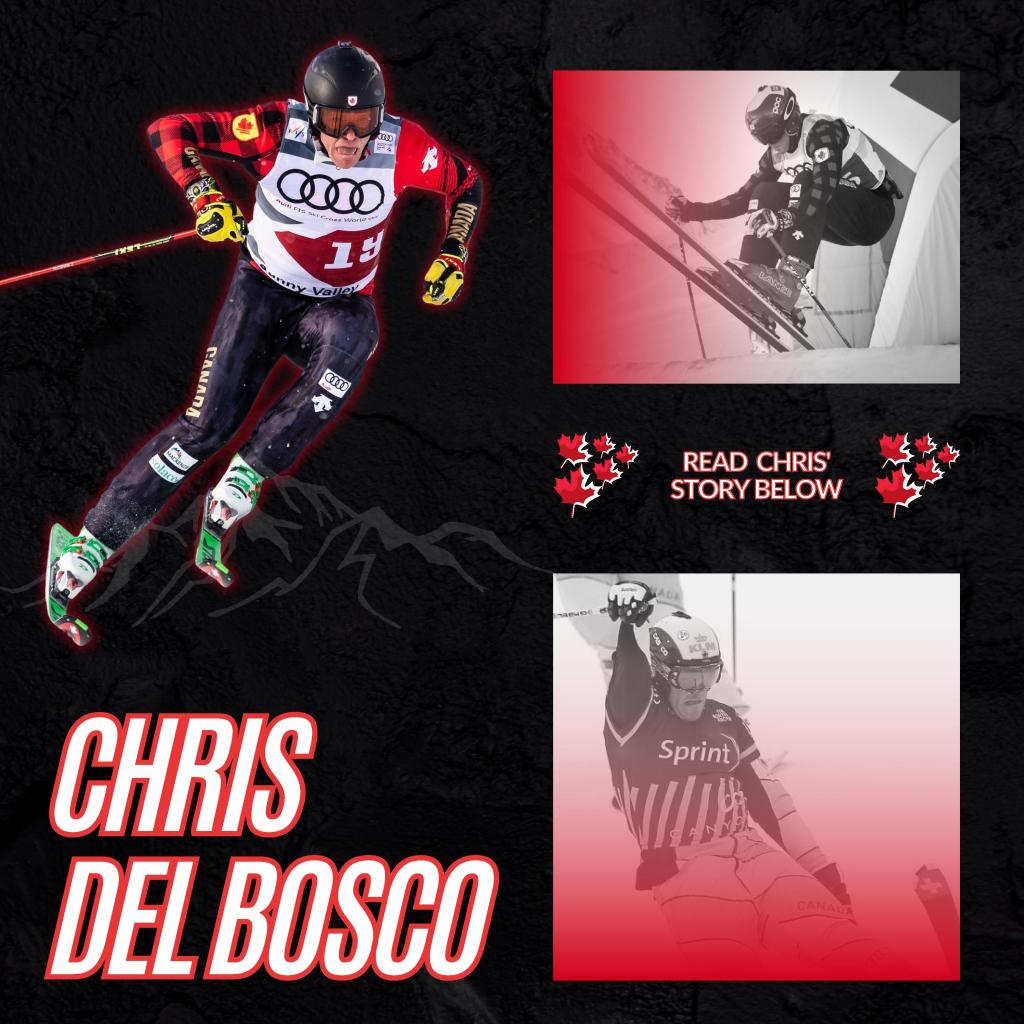

At that point, racing at three Olympic Games for Canada, winning 26 World Cup medals and building a national team to thrive on the world’s stage wasn’t in the cards. Yet in 2007, Del Bosco retained Canadian citizenship and represented the maple leaf for 15 years before returning to the U.S. this season to finish off his career.

The THC test, however, threw Del Bosco off the rails and into a downward spiral, drifting farther from skiing, hockey and the life he once knew.

As time passed, he drank every day before reaching the disaster in the creek. Nurses informed him that he narrowly avoided death, yet when he got up, all he could say was: “I’ll figure it out.” He was tentative to ask for help.

“He would always say that he would ‘figure it out,’ Centurioni said, “but he would never do anything.”

It took until the last of several drunk driving violations and a 10-day prison sentence to accept a new chapter. “That’s when it sank in that this could be a one-way ticket to a coffin if I don’t get myself together,” Del Bosco said.

He visited his sister in Los Angeles and eventually agreed to begin rehab on the outskirts of L.A., at not exactly the most pristine venue. However, as he worked through his alcoholism in the 90-day treatment, he found a part-time job at a bike shop in Laguna Beach, where the head mechanic was one of his first sponsors as a young kid racing bikes in Vail.

For Del Bosco, who hadn’t seen many things go in his favour for several years, there was a sliver of hope and factors turning his way.

After completing the program on New Year’s Eve in 2005, Del Bosco looked back to skiing. Ski cross had been invented just a few years prior and was a fixture at the ESPN X-Games. Days out of rehab and with no skiing or training for nine months, Del Bosco took on a last-chance qualifier, punched his ticket to Aspen, and stood on the podium mere weeks after leaving the Laguna Beach Rehab Centre.

While he thrived at the X-Games, his alpine career was all but dead, and there was no American ski cross program.

“I think I had a bright future in alpine ski racing, but chasing the next party or high became more important,” Del Bosco said. “The positive test was the nail in the coffin of my alpine career. I honestly felt like that was the end of my Olympic dream.”

In February 2007, with the Vancouver 2010 Olympics on the horizon, Del Bosco qualified for a Canadian passport through his late father Armando, giving him a chance to drive towards the Olympic dream that had seemed all but lost.

With the Olympic quadrennial at its dawn, Canada’s ski cross brain trust considered potential athletes. C.E.O. Cam Bailey and Del Bosco’s close friend and fellow ski cross racer Brian Bennett were out at dinner when a waiter asked what happened to Bennet’s arm that was in a sling.

He told the waiter he had crashed in the X-Games ski cross, only for her waiter to respond saying: “My husband’s cousin was in ski cross at X Games.” “Who?” Bennet asked. “Chris Del Bosco,” she responded.

The next day, Del Bosco’s phone rang — it was Bailey delivering the message that the Canadian team’s goal was to medal in Vancouver and that there could be a spot on the team for a dual citizen like himself.

Jumping at the opportunity, Del Bosco linked up with Bennett and other familiar faces Nik Zorcic and Stanley Hayer. The four formed the core of the first Canadian ski cross team to push the sport into the Olympics and within the realm of the Canadian skiing public.

“It was weird, starting to represent the country that I wasn’t born in, but it felt like a second chance that came out of nowhere,” Del Bosco said. “It was a fresh start, a fresh opportunity and a chance to reinvent myself while joining some guys I had skied with in the past.”

As the Olympics crept closer, Del Bosco’s stock rose on the world stage. In the 2008 season, his first on the World Cup, he ranked sixth in the world. In 2009, he finished the season ranked second — everything primed him to medal at the Olympics in Vancouver in front of a raucous Canadian crowd.

At those games, on a foggy day at Cypress Mountain, Del Bosco cruised through the preliminary stages. In the final, lined up alongside Michael Schmid, Andrea Matt and Audun Groenvold, Del Bosco started down the course with a devilish grin — he knew he had a chance to strike gold.

He got off to an okay start but slipped behind midway through the course and was settling into third place. Yet for someone who had fought to recover from addiction and injury, third wasn’t enough; he pushed for gold, only to fall on the final jump and finish fourth.

For one of the favourites on his adopted home snow, disappointment grew from what could have been a celebratory day.

“The top two had a bit of a gap. I was reeling them in and thought if I could nail the last couple of turns and scrub the hip jump, I would have a chance to get at least one of them,” he said. “ As I attempted to scrub some speed over the hip jump, my edges set, and it was game over.”

“I’ve never put third on a goal sheet. I felt there was a chance to improve my position, so I went for it, but it didn’t work out.”

While the third place was never in the plans, he rebounded well and won the world championship race in 2011. Yet, after the Vancouver crash, nothing quite seemed the same.

In 2012, in a race in Switzerland, Del Bosco was in a heat with four other racers. It was a rare five-person heat on a course that he and others had complained was too small. Indeed, the course was too dangerous.

At the start gate, Del Bosco lined up alongside teammate and close friend Nik Zorcic, but only he crossed the line — Zorcic suffered a violent crash and died instantly; he never finished the race.

“There were some tough times after Vancouver, even though he did so well in 2011,” said Centurioni. “When Nik died, that was tough. Chris won that heat and turned around to notice his best friend was dead. He instantly knew.”

“I don’t know how he ever got back in a start game after that.”

Yet that crash and death changed the sport for the better, making larger courses with less intense elements, giving Del Bosco a chance to thrive in a near-new sport and an opportunity to reinvent himself after heartbreak.

He continued to thrive on the World Cup circuit finishing 2012 in fourth overall and always contending through 2013 and 2014, despite a disappointing performance at the Sochi 2014 Olympic Games.

After Sochi, everything was going fairly smoothly for Del Bosco. He was thriving on the world stage and continuing to lead the Canadian team toward the PyeongChag 2018 Olympics. However, when he got there in what ended up being his final Games, he was beaten and bruised at the start gate. Yet, there was still a chance at gold.

Although coming into the competition as a favourite, his medal hopes quickly evaporated when he lost control of a large roller and forcefully crashed down to the snow, sending him to the hospital with four broken ribs and a bruised lung.

While his final Olympic race didn’t go to plan, Del Bosco recovered and won another silver medal for Team Canada at the World Cup. However, he never quite reached the heights he achieved before Pyeongchang 2018.

After missing out on Beijing 2022, the now 40-year-old realized there wouldn’t be space for him on the Canadian World Cup team in 2022-23. So, just as he’s done through his career, he bounced back and found yet another second chance by representing the USA for the first time since he was a teenager.

“It was sad to leave Team Canada; we’ve been through a lot of ups and downs and they’re really just supportive of me, no matter what I want to do,” Del Bosco said as he prepared to take on his first World Cup race as an American skier. “I wasted some opportunities when I was younger, and Canada came as a second chance, but now I feel I can return to the Americans to finish off my career.”

Chris Del Bosco was never supposed to become a sporting pioneer and one of the most successful Canadian skiers of all time. Yet at 41, as he pulls on a speed suit with stars and stripes, he looks towards building an American program and rounding off his own legacy.

Leave a comment